Thursday, March 28, 2013

Corporate profits remain strong

With today's release of revised GDP stats for Q4/12, we got our first look at corporate profits for the period. Although after-tax profits failed to post another record high, they have been increasing at a much faster pace than the overall economy for more than a decade. Since the end of 2001, profits are up 161%, for an annualized gain of 9.1%. In contrast, nominal GDP has grown by only 3.9% per year over that same period. It's rather amazing. Corporate profits have exceeded almost everyone's wildest dreams: since the end of 2008, profits have more than doubled.

I remember calculating back then that the market was priced to the expectation that about one-fourth of U.S. corporations would be bankrupt within 5 years, and that corporate profits would decline by almost two-thirds. In short, the market was priced to an end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it scenario. But here we are 4 years later, and instead of a huge collapse in profits, we have seen a doubling of profits! This explains the rise in the stock market in the past 4 years, even as the recovery has been the most miserable one on record: the future has turned out to be much better than expected.

But still the market remains pessimistic, extremely reluctant to believe the good times will last. Why? Here's one explanation: As the second chart above shows, profits have averaged just over 6% of nominal GDP for the past 50 years or so, and that has created the expectation that profits will inevitably revert to that mean.

The above chart shows the PE ratio of the U.S. stock market using total after-tax, adjusted corporate profits from the National Income and Product Accounts as the "E" and the S&P 500 index as the "P." (I've used a normalized S&P 500 index to make the ratio similar on average to the actual PE ratio of the S&P 500, which averaged a little over 16 during this same period.) Note that this measure of the PE ratio of U.S. corporations at the end of last year was about 30% below its long-term average. With the S&P 500 today reaching its former all-time closing high, and assuming corporate profits have not grown at all this quarter, this PE ratio today would be 11.8, still about 25% below the long-term average.

By this measure, stocks today are extremely attractive. (The conventional calculation of the PE ratio of the S&P 500, using 12-month trailing earnings, is 15.4 today, about 7% below its long-term average.)

What explains the undervaluation of stocks today? I think it's the expectation that corporate profits will revert to their historical average of about 6-6.5%% of GDP. This might take the form of corporate profits declining by one-third in the near term, or not growing at all for the next 10 years while nominal GDP posts average growth. Either scenario would qualify as extremely pessimistic, albeit consistent with a mean-reversion of profits relative to GDP.

Once again I'll advance the notion that while corporate profits appear to be unsustainably high relative to the size of the U.S. economy, they are at fairly average levels when compared to the size of the world economy. The U.S. economy today is much more integrated with the rest of the world than ever before, and for most large corporations, international sales are an increasingly important source of total profits. The global economy has grown much faster than the U.S. economy in recent decades, so it is only natural that U.S. corporate profits have also grown much faster than the U.S. economy. There needn't be a big mean reversion; profits might even continue to grow, or at least not decline relative to nominal GDP in the future.

Conventional thinking sees unsustainably high corporate profits and expects a reversion to the mean. Global thinking sees no a priori reason to worry at all.

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

Confidence: half full or half empty?

The Conference Board today reported that its March index of Consumer Confidence was much lower than expected (59.7 vs. 67.5). How should we interpret this?

My preference is to first put things in the proper perspective. That requires a chart like the one above.

Here's what I see in the chart: 1) this series can jump up or down by 5-10 points almost every month; therefore one month's datapoint does not tell you much at all. 2) the current level of the index is very depressed from an historical perspective, being at approximately the level that prevailed during the depths of the recessions in the early 1980s and the early 1990s. 3) the index has been rising, albeit irregularly, for the past four years.

I therefore conclude that what this indicator is telling us is that conditions, as perceived by the public, are gradually becoming less bad. Less bad, because confidence is still very low, and because things were even worse on balance for the past several years. So the proper way to see this is that pessimism is receding, not that optimism is rising.

This helps us to understand that the rise in the stock market is being driven much more by declining pessimism than by rising optimism. Put another way, the future has not turned out to be as bad as had been expected.

My preference is to first put things in the proper perspective. That requires a chart like the one above.

Here's what I see in the chart: 1) this series can jump up or down by 5-10 points almost every month; therefore one month's datapoint does not tell you much at all. 2) the current level of the index is very depressed from an historical perspective, being at approximately the level that prevailed during the depths of the recessions in the early 1980s and the early 1990s. 3) the index has been rising, albeit irregularly, for the past four years.

I therefore conclude that what this indicator is telling us is that conditions, as perceived by the public, are gradually becoming less bad. Less bad, because confidence is still very low, and because things were even worse on balance for the past several years. So the proper way to see this is that pessimism is receding, not that optimism is rising.

This helps us to understand that the rise in the stock market is being driven much more by declining pessimism than by rising optimism. Put another way, the future has not turned out to be as bad as had been expected.

Housing price update

Today's release of the January Case Shiller Home Price Index confirms what we have known for most of the past year: home prices have been rising, following the bursting of the housing "bubble." The housing market is emerging from its worst calamity ever.

This chart compares the Case Shiller home price index to the one compiled by the folks at Radar Logic. Case Shiller is seasonally adjusted, but the Radar Logic series is not. Nevertheless, the two have been tracking each other nicely. Case Shiller reports that home prices have increased 8% over the past year, while the Radar Logic series shows a 12% increase. Split the difference: it's a safe bet that home prices have risen about 10% on average in the past year.

The housing "bubble" was caused by excessive demand, fueled by artificially cheap credit, which caused prices to rise to unsustainable levels and housing construction to create a significant excess inventory of homes. It took six years of sharply reduced new home construction and an approximately 40% decline in real home prices to "fix" this mess. Supply and demand for housing have come back into balance, though we are seeing signs that housing may now be in relative short supply, which is why prices are once again rising.

As home prices have fallen, rents have increased, with the result that prices and rents are now back to a more reasonable relationship. It's taken six years, but market forces have brought things back into balance.

This chart compares the Case Shiller home price index to the one compiled by the folks at Radar Logic. Case Shiller is seasonally adjusted, but the Radar Logic series is not. Nevertheless, the two have been tracking each other nicely. Case Shiller reports that home prices have increased 8% over the past year, while the Radar Logic series shows a 12% increase. Split the difference: it's a safe bet that home prices have risen about 10% on average in the past year.

The housing "bubble" was caused by excessive demand, fueled by artificially cheap credit, which caused prices to rise to unsustainable levels and housing construction to create a significant excess inventory of homes. It took six years of sharply reduced new home construction and an approximately 40% decline in real home prices to "fix" this mess. Supply and demand for housing have come back into balance, though we are seeing signs that housing may now be in relative short supply, which is why prices are once again rising.

As home prices have fallen, rents have increased, with the result that prices and rents are now back to a more reasonable relationship. It's taken six years, but market forces have brought things back into balance.

Friday, March 22, 2013

The case for optimism

This post is the optimistic counterpart to my post yesterday, Why is everyone so gloomy? Here are 18 charts, in no particular order, that document the economy's ongoing recovery. I think this amounts to a persuasive body of evidence supporting my belief that the economy is recovering, and growing, and likely to continue to do so for the foreseeable future. It's not a robust recovery, to be sure, but it is definitely a recovery and things are indeed getting better.

Housing starts as of February were up fully 70% from their 2010 year-end level. That comes after starts fell to their lowest level in recorded history, where they remained for almost three years. This allowed a huge reduction in the supply of new housing which likely corrected for the excess of housing that was built in the heydays leading up to the bursting of the housing bubble. And despite the significant increase in new starts, the level of starts remains extremely depressed from an historical perspective. There is lots of room for further increases in the years to come. In anticipation of this, the stocks of major home builders are up 270% from their recession-era lows.

The current recovery was the only one in post-war history that began without a recovery in residential construction. With construction spending now increasing, this will provide important support for the economy in coming years. If residential construction returns to the levels that prevailed prior to the housing bubble, it could add as much as 3% to the growth of real GDP.

U.S. industrial production has almost fully recovered to its previous peak after suffering its worst decline in modern times. Production of business equipment is now at a new all-time high.

The unemployment rate is still high, and the economy needs to generate about 2 million more jobs just to get back to pre-recession highs, but as the chart above shows, jobs today are growing at about the same pace as they were in the mid-2000s.

A recession has never started without there first being a significant rise in unemployment claims. Today, claims continue their 4-year downtrend, strong evidence that the jobs market is getting healthier by the day.

Corporate profits are very close to all-time highs. The corporate sector has never been so profitable. Unfortunately, corporations lack the confidence to fully invest those profits, and the federal government has obliged by effectively borrowing from the capital markets just about all the savings that corporations have contributed over the past four years. But should confidence return, and policies improve (e.g., a reduction in the corporate tax rate, which is the highest in the developing world), corporations have the wherewithal to stage a powerful investment-led recovery.

Bank lending standards are still much tighter than they were before the recession, but it is a myth that businesses are unable to get loans. As this chart shows, bank lending to small and medium-sized business has been rising at double-digit rates for more than two years. On the margin, banks are more willing to lend, and businesses are more willing to borrow. This is a good barometer of increased business confidence in the future.

After a decline in the third quarter of last year, this indicator of business investment has turned back up, and is very close to attaining a new high level.

Housing prices are up as much as 10-12% in the past year. The inventory of unsold homes is close to its lowest level ever. Bidding wars are replacing foreclosures. The housing market has had plenty of time to adjust, and is now in a general upturn.

Consumers have made plenty of adjustments, with the result that households' financial burdens are at historical lows and consumer credit delinquencies are also at historical lows. This is a very encouraging development.

Household net worth is now at a new all-time high, thanks to rising stock prices, increased household savings, reduced debt, and rising home prices. All very healthy trends.

Thanks to new fracking technology, U.S. crude oil production is exploding to the upside, up almost 23% in just the past year. This is a huge industrial revival that has created boom conditions in North Dakota and Texas. Along with a gusher of new oil has come an abundance of natural gas, whose price has fallen relative to oil by orders of magnitude. U.S. industry now enjoys some of the world's cheapest energy. It's difficult to underestimate just how important this is to industrial America. It's a new age of energy abundance that is changing the face of entire industries. We are still in the early stages of this new boom.

This chart shows an index of key indicators of financial market liquidity and overall health. Markets have now fully recovered from the devastation of the financial crisis of 2008. Healthy and liquid financial markets are a necessary condition for a healthy and growing economy.

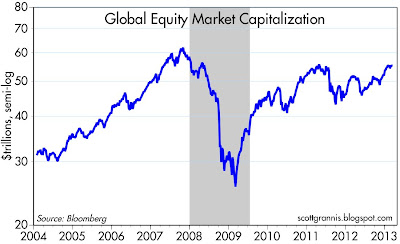

The recovery is not limited to the U.S. Global equity markets have rallied significantly in recent years (up almost $30 trillion), and are now only 11% below their pre-recession high.

Adjusted for inflation, retail sales are well into new high territory, having risen 3.2% in the past year.

Of course, there are still many problems the economy has to contend with. Monetary policy could become excessively easy if confidence returns and the Fed fails to take timely and aggressive steps to tighten policy. Fiscal policy continues to burden the economy with a very high level of spending relative to GDP, very high marginal tax rates, and the highest corporate tax rate in the developed world, although things are improving somewhat on the margin. Regulatory burdens are extremely high, with Dodd-Frank placing heavy burdens on the financial industry and the implementation of Obamacare threatening jobs and health coverage for millions of people across the country. Unemployment is still very high, and the labor force participation rate is disturbingly low. The unfunded liabilities of our major entitlements programs (e.g., Social Security, Medicare) are gigantic, and the current pace of spending growth is unsustainable over the long run. Public sector unions enjoy benefit packages that are bankrupting cities nationwide. Geopolitical tensions are rising in the Korean Peninsula and in the Middle East. Our federal deficit is still a shocking 7% of GDP and total debt held by the public is approaching an astonishing 80% of GDP.

And yet the private sector has dealt with the shock and disruption of a major recession and has survived, and is slowly but surely rebuilding the economy in spite of all these negatives.

It never pays to underestimate the ability of the U.S. economy to overcome adversity and grow. That's why I remain optimistic, especially because I see that markets are still obsessed by the negatives.

UPDATE: here's one more chart that I should have included before:

Auto sales have enjoyed a very strong recovery, having risen at an annualized rate of 14% from their low four years ago. Government attempts to "jump-start" sales in 2009 only caused a temporary uptick that was later reversed. The gains since then have been entirely "organic," driven largely by growth in hirings and incomes, increased confidence, and easier access to credit. No one expected sales to rebound this fast.

Housing starts as of February were up fully 70% from their 2010 year-end level. That comes after starts fell to their lowest level in recorded history, where they remained for almost three years. This allowed a huge reduction in the supply of new housing which likely corrected for the excess of housing that was built in the heydays leading up to the bursting of the housing bubble. And despite the significant increase in new starts, the level of starts remains extremely depressed from an historical perspective. There is lots of room for further increases in the years to come. In anticipation of this, the stocks of major home builders are up 270% from their recession-era lows.

The current recovery was the only one in post-war history that began without a recovery in residential construction. With construction spending now increasing, this will provide important support for the economy in coming years. If residential construction returns to the levels that prevailed prior to the housing bubble, it could add as much as 3% to the growth of real GDP.

U.S. industrial production has almost fully recovered to its previous peak after suffering its worst decline in modern times. Production of business equipment is now at a new all-time high.

The unemployment rate is still high, and the economy needs to generate about 2 million more jobs just to get back to pre-recession highs, but as the chart above shows, jobs today are growing at about the same pace as they were in the mid-2000s.

A recession has never started without there first being a significant rise in unemployment claims. Today, claims continue their 4-year downtrend, strong evidence that the jobs market is getting healthier by the day.

Corporate profits are very close to all-time highs. The corporate sector has never been so profitable. Unfortunately, corporations lack the confidence to fully invest those profits, and the federal government has obliged by effectively borrowing from the capital markets just about all the savings that corporations have contributed over the past four years. But should confidence return, and policies improve (e.g., a reduction in the corporate tax rate, which is the highest in the developing world), corporations have the wherewithal to stage a powerful investment-led recovery.

Bank lending standards are still much tighter than they were before the recession, but it is a myth that businesses are unable to get loans. As this chart shows, bank lending to small and medium-sized business has been rising at double-digit rates for more than two years. On the margin, banks are more willing to lend, and businesses are more willing to borrow. This is a good barometer of increased business confidence in the future.

After a decline in the third quarter of last year, this indicator of business investment has turned back up, and is very close to attaining a new high level.

Housing prices are up as much as 10-12% in the past year. The inventory of unsold homes is close to its lowest level ever. Bidding wars are replacing foreclosures. The housing market has had plenty of time to adjust, and is now in a general upturn.

Consumers have made plenty of adjustments, with the result that households' financial burdens are at historical lows and consumer credit delinquencies are also at historical lows. This is a very encouraging development.

Household net worth is now at a new all-time high, thanks to rising stock prices, increased household savings, reduced debt, and rising home prices. All very healthy trends.

Thanks to new fracking technology, U.S. crude oil production is exploding to the upside, up almost 23% in just the past year. This is a huge industrial revival that has created boom conditions in North Dakota and Texas. Along with a gusher of new oil has come an abundance of natural gas, whose price has fallen relative to oil by orders of magnitude. U.S. industry now enjoys some of the world's cheapest energy. It's difficult to underestimate just how important this is to industrial America. It's a new age of energy abundance that is changing the face of entire industries. We are still in the early stages of this new boom.

This chart shows an index of key indicators of financial market liquidity and overall health. Markets have now fully recovered from the devastation of the financial crisis of 2008. Healthy and liquid financial markets are a necessary condition for a healthy and growing economy.

The recovery is not limited to the U.S. Global equity markets have rallied significantly in recent years (up almost $30 trillion), and are now only 11% below their pre-recession high.

Adjusted for inflation, retail sales are well into new high territory, having risen 3.2% in the past year.

Of course, there are still many problems the economy has to contend with. Monetary policy could become excessively easy if confidence returns and the Fed fails to take timely and aggressive steps to tighten policy. Fiscal policy continues to burden the economy with a very high level of spending relative to GDP, very high marginal tax rates, and the highest corporate tax rate in the developed world, although things are improving somewhat on the margin. Regulatory burdens are extremely high, with Dodd-Frank placing heavy burdens on the financial industry and the implementation of Obamacare threatening jobs and health coverage for millions of people across the country. Unemployment is still very high, and the labor force participation rate is disturbingly low. The unfunded liabilities of our major entitlements programs (e.g., Social Security, Medicare) are gigantic, and the current pace of spending growth is unsustainable over the long run. Public sector unions enjoy benefit packages that are bankrupting cities nationwide. Geopolitical tensions are rising in the Korean Peninsula and in the Middle East. Our federal deficit is still a shocking 7% of GDP and total debt held by the public is approaching an astonishing 80% of GDP.

And yet the private sector has dealt with the shock and disruption of a major recession and has survived, and is slowly but surely rebuilding the economy in spite of all these negatives.

It never pays to underestimate the ability of the U.S. economy to overcome adversity and grow. That's why I remain optimistic, especially because I see that markets are still obsessed by the negatives.

UPDATE: here's one more chart that I should have included before:

Auto sales have enjoyed a very strong recovery, having risen at an annualized rate of 14% from their low four years ago. Government attempts to "jump-start" sales in 2009 only caused a temporary uptick that was later reversed. The gains since then have been entirely "organic," driven largely by growth in hirings and incomes, increased confidence, and easier access to credit. No one expected sales to rebound this fast.

Thursday, March 21, 2013

Why is everyone so gloomy?

It's fashionable to lament the economy's very slow recovery, which by some measures—notably the number of new jobs created—is the weakest in modern times. Even the Fed has succumbed to the pessimism that pervades the bond and stock markets. Yesterday the FOMC members revised downwards (albeit only slightly) their forecasts for growth. Real GDP this year is now expected to grow 2.3 – 2.8%, vs. a Dec. 2012 forecast of 2.3 – 3.0%; real GDP next year is projected to grow 2.9 – 3.4%, vs. an earlier forecast of 3.0 – 3.5%; and real GDP in 2015 is expected to grow 2.9 – 3.7%, vs. an earlier forecast of 3.0 – 3.7%. Over the longer run, the FOMC continues to expect growth of only 2.3 – 2.5%. I've used the average of those forecasts to generate the chart below.

If the FOMC members are right, then the economy is never going to return to its previous full-employment potential. For the 50 years leading up to the last recession, the U.S. economy grew at an annualized rate of about 3% per year. You can see that in the green line on the above chart. The FOMC's forecast (orange line) says we'll never return to that growth path. If that's not a pessimistic outlook, I don't know what is.

This pessimism can be seen in the TIPS market as well. 5-yr real yields on TIPS are trading at -1.72% today. That means that the purchaser of these TIPS (and by the way, the Fed is not buying TIPS at all, so it is arguable whether the Fed is artificially depressing TIPS yields) knows up front that he is guaranteed to lose 1.72% of his purchasing power every year for the next 5 years. Presumably, it only makes sense to enter into this transaction if one is extremely worried that alternative investments will yield even worse results. Furthermore, there is a form of arbitrage between the real yield on TIPS and the real growth of the U.S. economy. If one thought that the economy were going to grow 4% a year, would it make any sense at all to buy TIPS with a real yield of -1.72%? No, because an economy growing 4% a year is almost certain to throw off real returns that are well in excess of zero: it would thus be much better to buy a basket of stocks than to buy TIPS. As the chart above suggests, today's negative yield on TIPS is consistent with a market that expects real growth in the economy to be close to zero for the next few years. Note that when the economy was posting 4-5% real growth in the late 1990s, TIPS yields were 3-4%. If the Fed were absolutely confident that the economy would grow 2-3% over the next several years, would they be comfortable keeping short-term rates at zero? No. Which means that even though they "expect" real growth to be modest, deep down inside the FOMC members are very worried that if they don't "do something" growth might be closer to zero than to their current projections.

There are other telltales of gloom as well. The PE ratio of the S&P 500 is currently just over 15. That is significantly below its average of 16.6 since 1960, especially when you consider that corporate profits as a % of GDP are very near their all-time high. The only explanation of these facts is that the market expects profits to decline significantly in coming years. 30-yr Treasury yields—which are difficult if not impossible for the Fed to influence directly—are trading at just over 3%, which is very near their lowest level on record. Who would buy a 30-yr T-bond at 3% if he or she didn't expect nominal GDP growth to be 3% or less? With long-term inflation expectations fairly stable at 2.5%, that means long bonds are priced to the expectation of a miserable 0.5% annual real growth for as far as the eye can see.

For some reason, almost everyone—including the FOMC—seems to be assuming that the world changed dramatically in the year 2008, when the labor force participation rate (the percentage of the population that is either working or looking for work) suddenly started to decline, from 66% to today's 63.5% (see the second chart above). At the same time, growth in the labor force (those working or looking for work) flatlined. Call it the "new normal" if you will. But does this really have to be permanent? Demographics don't change like that overnight; perhaps the decline in the participation rate has more to do with a change in the incentives to work.

As the chart above shows, there was a sharp increase in the number of people receiving food stamps that began in early 2009. The number had been relatively flat for the previous two decades, but in the past four years the number of food stamps recipients has jumped by 50%. Two factors probably explain explain this: 1) the severity of the economy's decline in the 2008-09 recession, and 2) a relaxation of eligibility standards which took effect in the early weeks of the Obama administration. Although the average benefit per household today is only $277, it is possible that this has reduced the incentive of many workers to seek and accept a new job. But it's not a very convincing argument.

You've probably heard the stats: since Obama became president just over four years ago, there has been a net increase of only 1.4 million jobs, while the number of people receiving disability benefits has increased by 1.6 million. But as the chart above shows, the number of people receiving disability benefits has been growing at a fairly steady pace for the past 20 years: about 4% annualized per year (and I hasten to note that the number is up only 2.1% in the past year). Nothing unusual happened in this program that might explain the sharp decline in the labor force participation rate beginning in 2008. That's not to say we don't have a problem with the disability program, whose ranks have been increasing four times faster than the population for the past two decades, because we do. It's just that this has been an ongoing problem for a long time.

The chart above shows that there was a huge increase in federal spending as a % of GDP that began in late 2008. As I noted in a post last October, over 75% of the $840 billion allocated to "stimulus" spending in the 2009 ARRA was essentially devoted to transfer payments: taking from one person and giving to another. Only 8%, or $65.5 billion, was spent on transportation and infrastructure projects. In the post-war era, we have never seen an increase in government spending of this magnitude. So much money was handed out in such a relatively short period that it could conceivably have caused perverse incentives (e.g., rewarding those who weren't working) that encouraged people to "drop out" of the labor force. But when you consider that the huge increase in government spending was accompanied by a huge increase in regulatory burdens (e.g., Dodd Frank, Obamacare) and a huge increase in expected future tax burdens (a direct result of the doubling of the federal debt/GDP ratio since 2007, from 37% then to over 75% today—see second chart above), then we probably have enough ingredients for this to be an important driver of the tepid jobs market.

In short, companies are holding back on their hiring plans, worried about regulatory burdens and big increases in mandated costs. And many individuals have probably decided that the rewards to working harder or returning to work are outweighed by the costs (e.g., higher taxes) to doing so. (I for one have decided I'd rather work for free on this blog than pay a 65% marginal tax rate on any new income I might generate from starting a small business.) This article has a nice summary of what Obamacare means for many colleges and many small businesses: sharply increased personnel costs, reductions in hours worked, layoffs, increased disincentives to work. One can only begin to imagine the depressing effect of the prospect of significant increases in future tax burdens that have resulted from the huge increase in our federal debt burden in recent years: after all, spending is taxation, even if it is deficit-financed. And then there is the strong likelihood that much of the increased federal spending in recent years has been a waste of our economy's scarce resources. We've taken over a trillion dollars a year for four years and essentially flushed them down the toilet, spent on things that do not increase the economy's productivity and that reward leisure or inactivity instead of work or entrepreneurial risk-taking.

The huge growth in the size, scope, and burden of government is thus the most likely explanation for why we are living through a disappointingly slow recovery. There is hope for the future, however, since federal spending as a % of GDP is already down significantly in the past two years, and the federal deficit has already declined significantly as well (in both nominal terms and relative to the size of the economy), thanks to very slow spending growth and the ongoing recovery, which has boosted tax revenues. But for significant progress towards a healthier economy we will likely need to see outright reductions in regulatory burdens and in the growth of spending, particularly entitlement spending.

Cyprus contagion minimal so far

Fans of 2-yr swap spreads, which have been reliable coincident and leading indicators of systemic risk and economic and financial market health, will be pleased to know that the Cyprus bank deposit crisis has had only a very minor impact on swap spreads, both here and in the Eurozone. Message: not much to worry about here.

Claims data say the recovery is very real

Initial claims for unemployment have been declining for almost four years. They've been following the pattern set by every recession in the past 40 years. What's not to like? Claims are now within shouting distance of their all-time lows as a percent of the workforce and of the labor force. They are not likely to decline by much more. Businesses have just about finished tightening their belts; most businesses in the country have just about finished adjusting to the new realities of this economy.

The number of people receiving unemployment benefits has declined by 1.4 million in the past year, or 21%, and almost two million new jobs have been created in the past year. These are significant changes on the margin that happen only when the economy's health is improving. This is a genuine recovery, yet it seems that many people refuse to believe it because there remains a significant shortfall in the number of new jobs created. It may be a disappointingly slow recovery, but it is a recovery nonetheless.

Tuesday, March 19, 2013

Understanding the House budget plan

John Cogan and John Taylor have an easy-to-understand analysis of the House budget plan that will be voted on this week.

Most importantly, they explain why it is that a reduction in the growth of federal spending can actually stimulate economic activity. Traditional methods of analysis based on flawed Keynesian theories assume that any reduction in spending weakens the economy, and any increase strengthens it. One silver lining to the economic cloud of the past four years is that huge increases in spending (e.g., the ARRA) not only failed to stimulate growth but actually retarded growth. We've just lived through a laboratory experiment in Keynesian economics and found that the theory was dead wrong.

They also explain the importance of incentives, which are missing from Keynesian models, and make the very important point that "the resources to finance government expenditures aren't free—they withdraw resources from the private economy." Since the private economy spends its own money better than the government does, shrinking the size of government—especially when it is as large as it is today—leads directly to a more efficient and stronger economy.

Here's a quick summary of how the House budget plan would help boost economic growth immediately:

Most importantly, they explain why it is that a reduction in the growth of federal spending can actually stimulate economic activity. Traditional methods of analysis based on flawed Keynesian theories assume that any reduction in spending weakens the economy, and any increase strengthens it. One silver lining to the economic cloud of the past four years is that huge increases in spending (e.g., the ARRA) not only failed to stimulate growth but actually retarded growth. We've just lived through a laboratory experiment in Keynesian economics and found that the theory was dead wrong.

They also explain the importance of incentives, which are missing from Keynesian models, and make the very important point that "the resources to finance government expenditures aren't free—they withdraw resources from the private economy." Since the private economy spends its own money better than the government does, shrinking the size of government—especially when it is as large as it is today—leads directly to a more efficient and stronger economy.

Here's a quick summary of how the House budget plan would help boost economic growth immediately:

First, the lower level of future government spending avoids the necessity of sharply raising taxes. The expectation that tax rates won't need to rise provides incentives for higher investment and employment today.

Second, since the expectation of lower future taxes has the effect of raising people's estimation of future disposable income, consumption increases today. This change comes thanks to Milton Friedman's famous "permanent income" hypothesis that the behavior of consumers reflects what they expect to earn over a long period. According to our macroeconomic model, the higher level of consumption induced by the House budget's effect on consumer expectations is large enough to offset the reduced growth of government spending.

Third, the new budget's reduction in the growth of government spending is gradual. That allows private businesses to adjust efficiently without disruptions.

Households' finances continue to improve

According to the Fed's calculations as of the end of last year, U.S. households' financial burdens fell to the lowest level they have been in over 30 years. This comes thanks to rising incomes, belt-tightening, debt refinancing, deleveraging, and debt restructuring.

Note that the lines on the chart are the ratio of total monthly financial obligations (blue) and mortgage and consumer debt payments (red) to disposable income. The typical household now spends only 15.5% of its disposable (i.e., after-tax) income on auto leases, homeowners' insurance, property tax, mortgage payments, consumer debt payments, and rent. This is down from a high of 19% in the third quarter of 2007: that's a reduction of almost 20% in recurring monthly payment obligations relative to disposable income.

This is not only very impressive, but also very encouraging for the future, since it means that households' financial health is back on a much stronger footing, despite the fact that total employment is still far below where it was prior to the recession.

It never pays to underestimate the ability of the U.S. economy—and U.S. households—to cope with adversity and adapt to changing conditions. If only our government could do the same ...

Housing starts continue to improve

February building permits and housing starts continue to paint a picture of an industry that is rebounding strongly from extremely depressed levels. The level of new starts is still depressed from an historical perspective, having only recovered to levels that were previously associated with recessions. But the turnaround for this industry is still in its early stages, and it is now contributing to overall growth, as is typical in all past recoveries.

Starts in February exceeded expectations by a bit (917K vs. 915K), but prior months were adjusted upwards. Starts are now running at levels that are almost double what we saw at the 2009 lows. Since the housing recovery began gathering strength in the second quarter of 2011, starts are up over 65%. This is a huge and very significant change on the margin that is having ripple effects throughout the economy. Home Depot, for example, is up 130% since August 2011.

Building permits naturally lead starts by a few months, and they reached a new post-recession high of 946K in February. Since the low of 2011, permits are up over 75%. If the past is any guide, permits and starts could double from current levels over the next several years. As the chart below suggests, a recovery to that level could add as much as 3 percentage points to GDP (e.g., 1% per year for the next three years).

Monday, March 18, 2013

The Fed is not "printing money"

The idea that the Fed is "printing money" with abandon, and that this is seriously debasing the U.S. dollar, is a fiction borne of ignorance of how monetary policy actually works. Fed policy may indeed pose the risk of serious debasement in the future, but to date there is little or no evidence to suggest that this has occurred.

The above chart is a graphical depiction of how the Fed's balance sheet (in simplified form) has changed over the past six years, from a time in early 2007 when the economy was growing normally (although the housing correction was just beginning), to the situation today. The major changes: on the liability side, relatively normal growth of currency in circulation (see below for details), and gigantic growth in bank reserves; on the asset side, the elimination of T-bills, strong growth in T-bonds, and unprecedented growth and holdings of MBS and Agency securities. Put another way, the Fed has purchased about $2.36 trillion of T-bonds, MBS, and Agency securities, shed about $280 billion of T-bills, and in the process created $420 billion of new currency and $1.7 trillion of new bank reserves.

As the chart above shows, currency has grown at a 6.8% annualized rate since early 2007, the same rate that we have seen for the past 20 years. Currency actually grew at a faster rate from 1993 through 2003 than it has in the past six years, and the former was a period when inflation averaged 2.5%. In the past six years, inflation has averaged about 2.2%. So the recent growth in currency is nothing out of the ordinary, and does not necessarily imply higher inflation than what we have seen in recent decades. It is also important to note that the Fed only supplies currency on demand, in exchange for bank reserves. Thus, the Fed cannot "force-feed" currency to the world. The world holds only as much currency as it wants to hold, so growth in currency is not necessarily inflationary at all.

In addition to currency in circulation, the other major component of the Federal Reserve's liabilities is bank reserves, shown in the chart above. Here we see enormous growth, orders of magnitude in excess of historical experience. In fact, the Fed has expanded bank reserves by a factor of 18 in the past six years. Isn't this the same as "printing money?" No, because bank reserves aren't "money" and can't be spent anywhere. Bank reserves exist only as a liability on the Fed's balance sheet. Banks can exchange their reserves for currency, and currency can be spent, but as we saw above, currency has not grown by any unusual amount. Banks have instead been content to hold on to the majority of the reserves the Fed has created. This is due to the fact that the Fed started paying interest on reserves in 2008, which makes reserves functionally equivalent to T-bills, and the fact that banks have wanted to increase their capital and fortify their balance sheets, and bank reserves fit that bill.

In effect, the Fed has been doing nothing more than swapping newly-created bank reserves for bonds and currency, and the world and the banking system have been happy to participate in the swap. The Fed has taken duration risk out of the market and supplied low-risk and highly liquid assets in return. In a post last December, I described how in a way the Fed has been acting like the world's biggest hedge fund.

Banks can exchange their reserves for currency if the public demands it, or banks can hold on to their reserves if they want to increase their capital and fortify their balance sheets. The only other thing banks can do with their reserves is to support an increase in their deposits. In our fractional reserve banking system, banks must hold about one dollar of reserves for each ten dollars of deposits. Banks are the only ones who can "print money," and that is done by extending credit to borrowers. Given the increase in bank reserves, banks could theoretically have increased their lending and their deposits (which currently total about $8.7 trillion) by a factor of 18, or over $150 trillion. Obviously, nothing of the sort has happened.

As the chart above shows, the M2 measure of the money supply has grown only slightly more than 6% per year for the past 18 years. Since early 2007, M2 has grown at an annualized rate of 6.5%, about the same as currency. Again, there is no sign here of any usually fast growth as a result of the Fed's enormous expansion of bank reserves.

The proof is in the pudding: inflation by any measure has been averaging between 2 and 2.5% for the past six years, with no signs of any acceleration. We are thus forced to the conclusion that the Fed has not allowed any undue expansion of the money supply. Whatever growth in the amount of money there has been has only been slightly in excess of the world's increased demand for money and money equivalents, and that is why inflation has been relatively low.

As the chart above shows, the world's demand for M2 money has been extraordinarily strong in recent years. Since early 2007, M2 has grown 26% more than nominal GDP, with the result that the ratio of M2 to nominal GDP has reached its highest level since the late 1950s. Monetary policy has been enormously accommodative, but at the same time money demand has been exceptionally strong. It follows that if the Fed hadn't been so accommodative, we could have suffered deflation and/or a weak economy, since the economy would have been starved for liquidity.

Since November 2008, the fastest-growing component of the U.S. money supply has been savings deposits, which have increased 68%, from $4 trillion to $6.7 trillion. The enormous growth in savings deposits has almost certainly not been driven by their attractive yields (which have been close to zero), so it must be due to an overwhelming desire for liquidity and safety. Consumers have been deleveraging and increasing their money balances to an exceptional degree because they have become more risk-averse. Most of the growth in the money supply has been due to an increased demand for money and safety.

And just as consumers have worked hard to increase their money balances, banks have been very willing to hold on to the extra bank reserves the Fed has created, as they have struggled to boost their reserves and fortify their balance sheets.

In a sense, the Fed has spent most of the past 5-6 years responding to an unprecedented increase in risk aversion, which has manifested itself in a tremendous increase in the demand for cash, cash equivalents, deposits, and bank reserves. This increased demand for safety and liquidity has been the flip side of an equally unprecedented decline in confidence and an increase in risk aversion.

All of this leads to the following conclusion: since the Fed's quantitative easing efforts to date have been only sufficient to satisfy a huge increase in the demand for cash, cash equivalents, and bank reserves, what will happen when the demand for safe and liquid assets declines? When confidence in the future returns? When risk aversion declines? Will the Fed be able to reverse its quantitative easing efforts in a timely fashion, before an excess of reserves and a declining demand for cash pushes inflation higher? As I mentioned in a post last December,

Stephen Williamson discusses this same issue in great detail here, but from a slightly different perspective. The common thread we share is that the thing to worry about going forward is a declining demand for cash, cash equivalents, and bank reserves, since that could result in higher inflation if the Fed fails to take offsetting measures (e.g., draining reserves and/or increasing the interest it pays on reserves) in a timely and potentially aggressive fashion. There is no a priori reason to think they can't, but there is certainly reason to be worried, since we are sailing in uncharted monetary waters.

Unfortunately, it's ironic and paradoxical that the Fed's efforts to supply additional reserves to the banking system—at a time when the banks have many times more reserves than they could possibly want—may be doing just the opposite of what the Fed intends. Instead of boosting confidence, the Fed may be contributing to worries about the future course of inflation and interest rates. More reserves are not going to increase bank lending, since banks already face zero constraint on that score. Will more reserves increase confidence, or will they just increase concerns about the future?

It's not clear at this point what will happen as the Fed increases its purchases of Treasuries and MBS and creates more bank reserves in the process. But as long as uncertainty exists—and the Cyprus bank deposit fiasco threatens to increase risk aversion in the Eurozone—the demand for reserves is likely to remain strong and inflation is likely to remain subdued. As for the economy, it looks like it is slowly healing and taking care of itself.

The above chart is a graphical depiction of how the Fed's balance sheet (in simplified form) has changed over the past six years, from a time in early 2007 when the economy was growing normally (although the housing correction was just beginning), to the situation today. The major changes: on the liability side, relatively normal growth of currency in circulation (see below for details), and gigantic growth in bank reserves; on the asset side, the elimination of T-bills, strong growth in T-bonds, and unprecedented growth and holdings of MBS and Agency securities. Put another way, the Fed has purchased about $2.36 trillion of T-bonds, MBS, and Agency securities, shed about $280 billion of T-bills, and in the process created $420 billion of new currency and $1.7 trillion of new bank reserves.

In addition to currency in circulation, the other major component of the Federal Reserve's liabilities is bank reserves, shown in the chart above. Here we see enormous growth, orders of magnitude in excess of historical experience. In fact, the Fed has expanded bank reserves by a factor of 18 in the past six years. Isn't this the same as "printing money?" No, because bank reserves aren't "money" and can't be spent anywhere. Bank reserves exist only as a liability on the Fed's balance sheet. Banks can exchange their reserves for currency, and currency can be spent, but as we saw above, currency has not grown by any unusual amount. Banks have instead been content to hold on to the majority of the reserves the Fed has created. This is due to the fact that the Fed started paying interest on reserves in 2008, which makes reserves functionally equivalent to T-bills, and the fact that banks have wanted to increase their capital and fortify their balance sheets, and bank reserves fit that bill.

In effect, the Fed has been doing nothing more than swapping newly-created bank reserves for bonds and currency, and the world and the banking system have been happy to participate in the swap. The Fed has taken duration risk out of the market and supplied low-risk and highly liquid assets in return. In a post last December, I described how in a way the Fed has been acting like the world's biggest hedge fund.

Banks can exchange their reserves for currency if the public demands it, or banks can hold on to their reserves if they want to increase their capital and fortify their balance sheets. The only other thing banks can do with their reserves is to support an increase in their deposits. In our fractional reserve banking system, banks must hold about one dollar of reserves for each ten dollars of deposits. Banks are the only ones who can "print money," and that is done by extending credit to borrowers. Given the increase in bank reserves, banks could theoretically have increased their lending and their deposits (which currently total about $8.7 trillion) by a factor of 18, or over $150 trillion. Obviously, nothing of the sort has happened.

As the chart above shows, the M2 measure of the money supply has grown only slightly more than 6% per year for the past 18 years. Since early 2007, M2 has grown at an annualized rate of 6.5%, about the same as currency. Again, there is no sign here of any usually fast growth as a result of the Fed's enormous expansion of bank reserves.

The proof is in the pudding: inflation by any measure has been averaging between 2 and 2.5% for the past six years, with no signs of any acceleration. We are thus forced to the conclusion that the Fed has not allowed any undue expansion of the money supply. Whatever growth in the amount of money there has been has only been slightly in excess of the world's increased demand for money and money equivalents, and that is why inflation has been relatively low.

As the chart above shows, the world's demand for M2 money has been extraordinarily strong in recent years. Since early 2007, M2 has grown 26% more than nominal GDP, with the result that the ratio of M2 to nominal GDP has reached its highest level since the late 1950s. Monetary policy has been enormously accommodative, but at the same time money demand has been exceptionally strong. It follows that if the Fed hadn't been so accommodative, we could have suffered deflation and/or a weak economy, since the economy would have been starved for liquidity.

Since November 2008, the fastest-growing component of the U.S. money supply has been savings deposits, which have increased 68%, from $4 trillion to $6.7 trillion. The enormous growth in savings deposits has almost certainly not been driven by their attractive yields (which have been close to zero), so it must be due to an overwhelming desire for liquidity and safety. Consumers have been deleveraging and increasing their money balances to an exceptional degree because they have become more risk-averse. Most of the growth in the money supply has been due to an increased demand for money and safety.

And just as consumers have worked hard to increase their money balances, banks have been very willing to hold on to the extra bank reserves the Fed has created, as they have struggled to boost their reserves and fortify their balance sheets.

In a sense, the Fed has spent most of the past 5-6 years responding to an unprecedented increase in risk aversion, which has manifested itself in a tremendous increase in the demand for cash, cash equivalents, deposits, and bank reserves. This increased demand for safety and liquidity has been the flip side of an equally unprecedented decline in confidence and an increase in risk aversion.

All of this leads to the following conclusion: since the Fed's quantitative easing efforts to date have been only sufficient to satisfy a huge increase in the demand for cash, cash equivalents, and bank reserves, what will happen when the demand for safe and liquid assets declines? When confidence in the future returns? When risk aversion declines? Will the Fed be able to reverse its quantitative easing efforts in a timely fashion, before an excess of reserves and a declining demand for cash pushes inflation higher? As I mentioned in a post last December,

... the biggest risk we all face as a result of the Fed's unprecedented experiment in quantitative easing is the return of confidence and the decline of risk aversion. If there comes a time when banks no longer want to hold trillions of dollars worth of excess bank reserves for whatever reason (e.g., the interest rate the Fed is paying is no longer attractive, or the banks feel comfortable using their reserves to ramp up lending, or the public no longer wants to keep many of trillions of dollars in bank savings deposits), that is when things will get "interesting."

Stephen Williamson discusses this same issue in great detail here, but from a slightly different perspective. The common thread we share is that the thing to worry about going forward is a declining demand for cash, cash equivalents, and bank reserves, since that could result in higher inflation if the Fed fails to take offsetting measures (e.g., draining reserves and/or increasing the interest it pays on reserves) in a timely and potentially aggressive fashion. There is no a priori reason to think they can't, but there is certainly reason to be worried, since we are sailing in uncharted monetary waters.

Unfortunately, it's ironic and paradoxical that the Fed's efforts to supply additional reserves to the banking system—at a time when the banks have many times more reserves than they could possibly want—may be doing just the opposite of what the Fed intends. Instead of boosting confidence, the Fed may be contributing to worries about the future course of inflation and interest rates. More reserves are not going to increase bank lending, since banks already face zero constraint on that score. Will more reserves increase confidence, or will they just increase concerns about the future?

It's not clear at this point what will happen as the Fed increases its purchases of Treasuries and MBS and creates more bank reserves in the process. But as long as uncertainty exists—and the Cyprus bank deposit fiasco threatens to increase risk aversion in the Eurozone—the demand for reserves is likely to remain strong and inflation is likely to remain subdued. As for the economy, it looks like it is slowly healing and taking care of itself.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)